Why do developers do such s***** design?

Some thoughts on good design...for real estate development

The Story

As an architect who has written a book about developers with the word “design” in its subtitle, I am often asked by my architect friends and colleagues, “Why don’t developers do better design?” (That is a more generous version of the question.) My sense is that this is actually several questions, wrapped together, including: “Why don’t they have good taste in design?” “Why don’t they spend more money to do good design?” and “Why don’t they hire me and listen to me so that I can help them do good design?” The question presumes that architects know best what good design is and that developers are ignorant of it. But the question also ignores a bigger issue, which is that good design, like “good taste,” is subjective, and that many other people involved in the development process have their own ideas of what good design looks like. I would suggest that we architects can best serve our clients—and their users—when we accept the challenge of integrating these other perspectives into our designs. That’s why I often reply to my architect friends and colleagues by saying, “The better question is, ‘What does good design for development look like?’” We can begin to answer this question by looking at design through the lenses of environmental psychology, architectural criticism, and market research—the buyers—as well as the other participants in the process, and of course, the developer.1

The Theory

Environmental Psychology: Since the 1960s, researchers in the field of environmental psychology have studied how different types of people experience buildings and places. In one study that asked architects and non-architects to rank photos of homes in two design styles, “high” and “popular,” the architects favored complexity and high style, but non-architects favored simplicity and popular motifs. A similar study considered “objective characteristics” (physical cues, like arches, articulation, balconies, canopies, color variety, columns, ornament, glass, landscaping, metal, people, roof pitch, railings, roads, rounded shapes, sculpture, stone, brick, number of stories, triangles, stepped massing, size, etc.) and “subjective ideas” (impressions, like clear, complex, friendly, meaningful, rugged, etc.). This study found that while architects focused on objective characteristics, what really mattered to non-professionals was “subjective ideas” of what a place is like. In fact, the big finding in this study was that, while architects and nonarchitects agreed that “a meaningful building is an aesthetically good building,” the two groups used none of the same cues in deciding what was “meaningful,” and, in fact:

“There was ‘zero agreement’ between architects and non-architects on what was a ‘meaningful building.’”

Together, these and other studies conclude that the professional training and socialization of architects (and planners, too) emphasize the technical and material qualities of the built environment, and discourage a personal and subjective approach. In other words, our educations and experiences as architects change us, and we do not see buildings and the built environment the same way our clients and users do.

Architectural Criticism: Many architectural critics have trained in architecture (see above), and while they presume to speak for good design, their critiques are written just after a building has been completed and are usually based on their own style preferences. As a result, they rarely reflect the user’s view because there has not been enough time for user feedback. By comparison, post-occupancy evaluations (POEs) completed years after a building or place has been occupied, don’t measure “style” but rather, whether a building functions well and is satisfying to the users as a place to live or work. This sets up a paradox, where a building that users think is good after years of use can be condemned on opening day by a critic based on style preferences. And remember, architectural critics are usually addressing a narrow audience: Architects and other architectural critics. [Forsyth]

Market Research: Potential buyers of residential real estate also have a say in what constitutes good design, but while they may have a long list of preferences—layout, finishes, appliances, bathrooms, kitchen, daylight, balcony, amenities, etc.— the three things that matter most are: Price, product, and location (the same goes for multi-family, office, retail, and industrial real estate buyers and tenants). Price means “chunk price”—the price I know I can finance (dollar-per-square-foot prices mean little to actual buyers); product means “layout”—a unit that serves the needs of me and my family, including numbers and types of rooms; and location means neighborhood, school district, and proximity to my job, my kid’s school, parks, transit, etc. But where does design fit into this equation? According to market research experts, buyers have become more design-savvy in recent decades, and some are now familiar with globally known “Starchitects.” This heightened sensitivity means that good design matters, and even more so in a down market, where it may provide a competitive advantage. However, “cutting-edge” or “love-it-or-hate-it” designs do not translate to the broader market. It is also risky to design for an idealized version of a sophisticated “target buyer” and better to be attractive to a broad cross-section of the market. More generally, good design cannot correct for pricing problems: If your product costs 20% more than the one across the street, people will not pay extra for it, regardless of how good the design is. Although we may not like it, we architects need to remember that price remains the bottom line in real estate development.

Everyone else: In addition to buyers, there is a long list of other people who care about design and think they know what good design looks like, and have an influence on the design that is not always visible to the architect or the rest of us. City planners, elected officials, community organizations, and nearby residents have a direct influence on approvals and entitlement processes. (Neighbors can also be a good source of market research, and, in fact, some may be future buyers.) Lenders underwriting the loan and investors also have influence, as their money is at risk, and they have their own opinion on what will sell, from unit mix to number of parking spaces. The developer must satisfy all of these people while keeping his eye on the future buyer, because what the developer wants is a project that sells—and sells out.

At a more fundamental level, there is often a disconnect between the architect’s view and the developer’s view, which must account for the project’s economics. Chicago architect and developer Jim Lowenberg tells a story about being challenged by an architectural critic who asked him why he was putting marble on the thresholds and countertops in the units when he could have put better finishes on the façade of the unadorned concrete parking garage.

“I guess it was heresy when I said, ‘because people don’t care what a garage looks like and in fact, they would rather see a marble or granite countertop in their unit than a magnificent garage.’”

In a similar story, a Minneapolis developer I know grew up in the hospitality industry and regularly surveys his tenants on everything from the quality of the janitorial services to their unit layouts and even their windows. The last question on one survey was, “What color is the outside of the building?” The answer: Nobody knew.

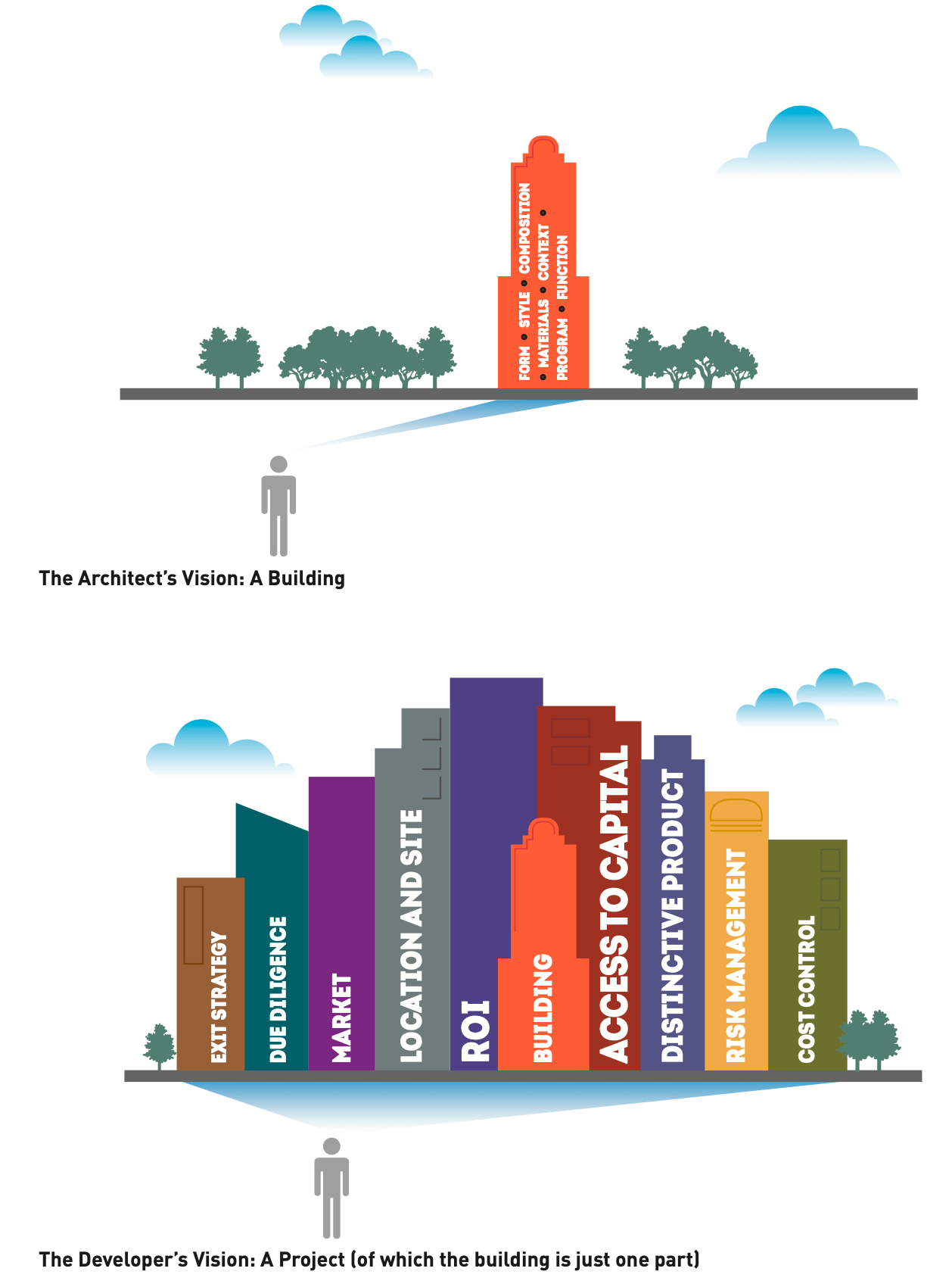

Two different perspectives. Around the time my book, How Real Estate Developers Think, was published in 2015, I did a presentation at the annual conference of the Minnesota Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. In preparation for the talk, I designed a pair of diagrams that illustrate the difference in perspective between the architect, who views the building as the end, and the developer, who views the building as a means to an end. For the architect, the building is architecture. For the developer—and their lenders and investors—the building is an investment vehicle that balances rate of return with level of risk over an anticipated ownership period. Good design is an important ingredient in a successful development project, but it is not the only ingredient. Only by considering the many other factors that go into a successful project can an architect understand where good design fits into the larger development process.

The Lesson

Beauty, or in this case, good design, is in the eye of the beholder. Most developers actually do value good design—because it sells—but they see it through the eyes of the many other actors involved in the process, including the buyers. Architects who hope to work successfully with these developers must learn to see design through all of those eyes as well. And last but not least, the economics really do matter: In a competitive market, cost, price, and value are connected, and our job as architects is to add value without increasing cost (which we should be able to do if we are as good as we think we are). Only after we accept that challenge can we expect to play a lead role in designing the real estate projects that shape our communities.

“The person who looks to buy or rent a unit in a high-rise only cares about three things: The location of the building, the layout of the unit, and the view from their unit. They don’t care as much about the physical appearance of the building, and it is my contention that they never look above the third floor.”

- Jim Loewenberg

“Always design for your client’s client.”

- Morris Lapidus, Miami Mid-Century Modern architect of the Fontainebleau and Eden Roc hotels on Miami Beach

Much of what follows, including citations, can be found in my book, How Real Estate Developers Think: Design, Profits, and Community, Philadelphia: Penn Press, 2015, Chapter 5, “Good Design,” pages 119-130, and endnotes, page 304.